Johannesburg’s business centers surrounded by slums (Image credit: Juda Ngwenya/Reuters)

by Elbay Alibayov | Political risk series

The leadership deficit, resource curse, and inequality

Last month, the 6th Tana Forum (Tana High-Level Forum on Security in Africa) held in Ethiopian city of Bahir Dar brought together former and current heads of state, government officials, diplomats, academics and civil society representatives to discuss the natural resource governance. As ever, the topic of the continent’s resource curse was in the focus. What was new, however, is that this time around the African leaders seemed to acknowledge (with initial hesitation though) that it is them who must bear the greatest responsibility for, as former Nigerian President and incumbent chairman of Tana Forum, Olusegun Obasanjo put it, “the way and manner natural resources are exploited and how revenues from them are harnessed and expended [that] have allowed social and political divisions to fester.” Thus, the old narrative pointing finger at usual suspects—foreign investors and multinational extractive companies—being primary and sole culprits started finally changing.

Just ten days later, the issue of serious leadership deficit was echoed at yet another high-profile event, the World Economic Forum held in Durban. Here, the South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma in his address to participants put the blame of persistent inequality across the globe, and particularly in Africa, on political elites and governments: “As leaders, we have not addressed adequately how we are going to close the gap between rich and poor in the world and achieve meaningful, inclusive growth.” He went further by calling the African leaders and the international community to combat economic crimes, such as money-laundering and profit-shifting.

These are all broad topics and they have their country-specific root causes and present-day circumstances, but the point about local political leadership seems correct. When there is no political unity among key local players, when they are corrupt and together with their supporting clans try to coerce and dominate anyone else in the land, then their countries fall easy prey to various external actors, who take advantage of them. So the problem of “curse” should start with local leadership—if they abide by the land’s laws and serve their people with integrity, the chances are tiny for economic crimes and corruption to take a massive scale and become a systemic societal decease.

The list of economic crimes the African countries are actively engaged in is long and their scale is at times striking. In this piece I will share my initial findings and thoughts pertaining to one of them—that is illicit capital flight from and to sub-Saharan area of the continent. I was particularly interested in finding any relations between the illicit financial flows (IFF) and economic inequality, as one prime source (whether cause or exacerbating factor) of conflict and instability. No big theories, no conclusive statements—just an attempt to make sense of available evidence. The piece therefore, following Schopenhauer’s method, “by no means attempts to say whence or for what purpose the world exists, but merely what the world is.”

The recent emphasis in global and regional discourse, on the consistent lack of leadership in Africa is not incidental. If not for violent power struggles of political elites and corrupted practices in public institutions (and their local and foreign business accomplices) the continent’s countries would have been more socially stable, the well-being of their citizens higher, and their economies less vulnerable to external shocks. The real curse of Africa is its political institutions, not resources.

Illicit financial flows: trends, size and composition

A series of reports published by Global Financial Integrity (GFI) , the Washington DC-based research and advisory organization provide estimates of the illicit flow of money in and out of the developing world. For example, GFI’s estimates show that “since 1980 developing countries lost US$16.3 trillion dollars through broad leakages in the balance of payments, trade misinvoicing, and recorded financial transfers. These resources represent immense social costs that have been borne by the citizens of developing countries around the globe.”

Individual sub-Saharan countries do not appear among top ten in the lists of either illicit inflow or outflow transfers in 1980-2012. Overall, compared to other regions sub-Saharan Africa has not been in the leading role in this business either; in absolute numbers much more has been taken from Asia, for example. In 2014 alone the outflows from sub-Saharan economies are estimated at between US$36 billion and US$69 billion and inflows between US$44 billion and US$81 billion. Therefore, overall IFF volume for sub-Saharan Africa is estimated at between US$80 billion and US$150 billion (midpoint US$115 billion). This makes the portion of sub-Saharan Africa in the global two-way illicit flows for that year very modest – a bit more than 6.5 percent.

However, this may be misleading. First, the global estimated capital flights (and those for Asia, in particular) are very much inflated because of China; thus each region’s contribution, when excluding China, would be much higher. Second, much more relevant is not the comparison with other regions but within the sub-Saharan part of the continent. And even here, by the size of economy and its growth rate and other indicators the economies of sub-Saharan Africa diverge greatly.

Vast majority of sub-Saharan economies are small. These countries are also poor; many are very poor in fact (as of March 2016, out of 39 Heavily Indebted Poor Countries across the globe, 32 were in Africa; all but Sudan were in sub-Saharan part). And therefore those numbers translated into percentage of total trade or compared to GDP per capita tell a different story—those sums are direct losses, the money the Sub-Saharan poor are robbed of, and they are felt with much severe pain than significantly larger IFF sums in more prosperous parts of the world. The amount of one hundred and fifteen billion US dollars in one year is no small amount of money anywhere on this planet; for sub-Saharan Africa, the region home to almost half of the world’s extremely poor—this is an enormous amount of money. Just try to imagine the “opportunity cost”—what else this money could have been spent on. It hurts.

And finally, trend is important. And here we have a mixed picture. On the one hand, the region has evidenced the highest rate of average annual IFF (outflows and inflows combined) for years 2005-2014: it is estimated (in midpoint terms) at approx 20 percent of total trade (average for all developing countries being 19 percent). On the other hand, and this is the only good news here, sub-Saharan Africa demonstrates a higher descending trend over the same decade: its rate has dropped from 22.8 percent in 2005 to 16.6 percent in 2014, while the rate for all developing countries has decreased from 19.5 percent to 18.8 percent, respectively.

Another difference of interest: in the course the decade 2005-2014, in all regions but sub-Saharan Africa the illicit capital inflows were approximately twice as large as outflows. In sub-Saharan Africa they were almost equal. The outflows/inflows had the following composition: 9.5 v 10.4 in percentage points (9:10) in sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 5.9 v 13.2 percentage points (1:2.2) for all developing countries. And even here the region is not homogeneous: for example, Mozambique and Cameroon both averaged at around IFF 7-7.5 percent of total trade in the course of 2005-2014; while the former had outflows/inflows composition as 2.5 percent and 5.0 percent, and the latter the reverse– 5.5 percent and 1.5 percent of the respective country’s total trade.

It is difficult to say with precision in the absence of additional data, but the difference seems in the purpose the developing countries are being used for either inflows or outflows of illicit capital. The countries of sub-Saharan Africa appear to be primarily siphoning the money out of their economies while being less attractive for money laundering and external investment (or reinvestment) in grey economy than other regions.

Irrespective of comparative absolute amounts, the illicit capital flights have probably been more painful to sub-Saharan Africa’s populations, in first hand poor, than in other regions of the world. Transferred through formal (recorded) channels, this money could have contributed to tax revenues and directed to strengthening social safety networks, pro-poor programmes and job creation, to benefit their citizens.

Assets in tax heavens vs. Official Development Assistance

One of the most shocking findings pertaining to (financial) relationship between developed and developing countries revealed in the recent reports is that for long time, “developing countries have effectively served as net-creditors to the rest of the world with tax havens playing a major role in the flight of unrecorded capital.” For example, in 2011 (most recent year of available data) holdings of total developing country wealth in offshore financial centers were valued at US$4.4 trillion. In the GFI assessment, “there is perhaps no greater driver of inequality within developing countries than the combination of illicit financial flows and offshore tax havens. These mechanisms and facilitating entities benefit the rich—we call them the ‘1 percent’ for convenience—and harm the middle class and poor.”

The sub-Saharan African countries could have been much less dependent on external financial assistance while the quality of life of people living in those countries could have been tangibly higher. This is an issue of choice for political leadership, nothing else.

As the report shows, residents of developing countries held US$1.8 trillion in tax heavens in 2005 which increased to US$4.4 trillion in 2011. Sub-Saharan Africa’s share in that was rather modest, but the region’s assets held in offshore financial centers kept growing at the record rate of over 20 percent annually (almost four time the world average), in the course of 2005-2011. This (at least in part) explains the difference between sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the developing world in terms of outflow/inflow ratio of capital flights mentioned above.

There is even more surprising finding. Already in 2011 the total amount (foreign direct investment and private investment) of sub-Saharan Africa’s assets held in tax heavens was five times the official development assistance (ODA) from all sources (official development assistance, as well as other official and private funds) disbursed to the region the same year (US$52.6 billion : US$263.04 billion = 1:5). Actually, the total amount of ODA to sub-Saharan Africa in four years of 2012-2015 (according to OECD DAC data) equaled to US$252.26 billion which is less than the amount of assets from the region held in tax heavens the year before, in 2011. And the offshore investments kept growing since.

The very fact that a country is receiving quite significant amounts of international assistance in the form of technical advice and development programmes, loans, grants etc from public and private sources, and at the same time its corrupted politicians and their “business partners” (part of so called one percent) are pumping out amounts of money its five-fold (!) that has been illegally earned in the same country at the same time, to offshore accounts—is outrageous.

Diversity as it is

Of course, not all sub-Saharan countries are infected with this decease. So it would be correct (as in any other respect) to distinguish between those countries where illicit capital flight is massive and persistent and those where it is relatively small and/or random (similarly, say to the difference between “systemic” corruption and individual, sporadic instances of corrupt practice). There are countries like Mauritania and Angola (average 1 and 5 percent per annum over the decade of 2005-2014, respectively), and there are the region’s mid-performers like Nigeria (with estimated average 20 percent) and front-runners like Benin (average 114 percent of total trade). And then there is Liberia, the world champion and the current record holder—with estimated annual illicit capital flights at staggering 1,000 percent (i.e. ten-fold) of the country’s total trade over the decade, 2005-2014. To compare, the next to it in the global rankings are Aruba and Panama, with the rate twice less than that of Liberia.

Therefore, it makes sense to categorize the countries in terms of the economy’s size, income, growth rate, resource intensity, economic and social inequality, regime type and other indicators and compare them against the categories based on the IFF range—to find out how, if at all, they correspond to each other. That is what I entertained, and found this exercise quite insightful. The untidy thoughts on some of those comparisons will be presented in the next piece. Herein is the first set, by the economy’s size.

And one last note before we move forward. Individual characteristics and circumstances matter, of course. One of few countries falling under Very Low/Low category of IFF (0<3<5 percent of total trade) is Somalia, for example. It would be very naive to consider this low IFF range registered as representative of healthy economy and responsible leadership. What we know of Somalia for prolonged period of time has been quite the opposite. That is why the findings on country groups by certain criteria presented below and in the forthcoming piece are merely first impressions; those findings shall be looked at closely on a case-by-case basis to take into account the country-specific features, in order to arrive at plausible explanations.

Illicit financial flows vs. size of economy

To start with analysis, we first have to categorize the sub-Saharan African countries by the IFF ranges. In so doing, I refrained from building the (whatever imprecise and conditional) scale based on the global rankings. As explained above, the sub-Saharan region has its own characteristics, quite different from the rest of the world, and therefore what is considered as “low” here may be ranked as “medium” or “high” in other regions or on the global rankings.

I kept it simple. The countries of the region (47 altogether) divided into the following categories by the medium point value of their average annual IFF, as percentage of the respective country’s total trade in the same period (2005-2014): Very Low (0-3 percent); Low (3-5 percent); Medium (5-8 percent); High (8-10 percent); and Very High (above 10 percent). Given the conditionality of such a ranking, I also introduced borderlines, like Low/Medium, High/Very High, etc. to add more flexibility to the categorization.

Here is the full list by IFF categories, 2005-14:

–Three countries in Very Low category: Eritrea, Mauritania, Somalia;

–None in Low category;

–One country in Low/Medium category: Angola;

–Three countries in Medium category: Cameroon, Lesotho, Mozambique;

–None in Medium/High;

–One country in High category: South Africa;

–Twenty-one countries in High/Very High category: Botswana, Cabo Verde, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, Kenya, Madagascar, Namibia, Seychelles, Swaziland, Tanzania; and

–Twenty-nine countries in Very High category: Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia , Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

The vast majority of countries in sub-Saharan Africa belong to the categories with high and very high illicit capital flight rates (above 8 percent of a country’s total recorded trade, and in many cases far beyond this benchmark, growing up to tens and hundreds of percent) by both the continental and global standards. No one appears to be immune to this corrupt and incredibly damaging practice.

I will use this categorization throughout the exercise. As it is clear from the list, 85 percent of sub-Saharan African countries belong to the categories demonstrating High and Very High rates of illicit capital flight, during the period studied.

Table below gives an idea of the diversity, depth and scale in terms of the correspondence between the IFF and the economy size (please note that there are no criteria behind selection, it is just a random collection for illustrative purpose). I used the World Bank data on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for 2014 (as the last year in the period observed) as an indicator/measure of economy size.

It appears that there is no clear correspondence between the size of an economy and its IFF range. It especially concerns the High and Very High categories, where all economies, big and small, are represented.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, all but Somalia are exersizing, to varying degree, the illicit financial transactions. There is no obvious correspondence between the size of economy and the range of illicit capital flight. Economies of all size, from tiny to large, are represented in the categories characterized by especially high rates of illicit capital flight. This means that the size of economy is not a determining factor in illicit financial flows from and to Sub-Saharan Africa.

* * *

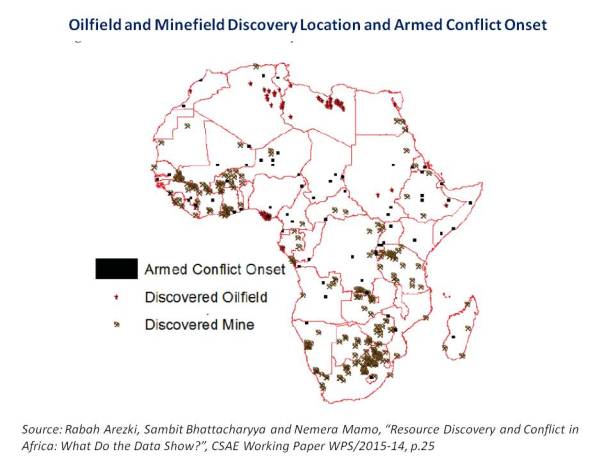

I hope you are enjoying the ride. In the piece forthcoming I will share my untidy thoughts on the relations (or not) between the illicit financial flows in sub-Saharan African countries and such characteristics as the economy’s resource intensity and income level, poverty rates and shared prosperity, as well as the political regime type. Stay tuned!

For those who missed the first part in a series, here is the link.